Chili fences and insurance schemes curb rising human-wildlife conflict

By Brian Ochieng Akoko, Reporter | Nakuru City – Kenya.

The success of African conservation is often measured by the number of rhinos or elephants counted in a protected area. But the true measure of success is found on the farm boundaries.

It is found in the villages that border the national parks. Here, conservation is not a statistic. It is a daily, visceral challenge. It is the challenge of human-wildlife coexistence.

As human populations expand and land use intensifies, the historic buffer zones are shrinking. Animals, driven by instinct and hunger, inevitably cross paths with people. This leads to conflict. A lion kills livestock.

An elephant raids a season’s worth of maize. A farmer, defending a livelihood, retaliates. This conflict is the single greatest threat to long-term conservation in Africa.

It undermines the goodwill of the people who live with the price of proximity. A new era of conservation is emerging. It recognizes that preserving wildlife is impossible without the full economic and social support of local communities.

This era is powered by innovative, non-lethal solutions. It seeks to reduce conflict. It aims to turn wildlife from a liability into an asset. This movement is built on local wisdom. It uses simple technology. It is a vital effort to help communities and megafauna share space.

The High Cost of Coexistence

The cost of living alongside wildlife is immense. For a smallholder farmer, losing a cow to a predator can wipe out their annual income. Losing a harvest to elephants can mean immediate hunger.

In communities surrounding major conservation areas, the economic burden of this coexistence is overwhelmingly borne by the poorest residents. This disparity fuels resentment.

It creates a deep, fundamental disconnect between the goals of conservationists and the needs of local people. For generations, the model was to build fences. To create hard boundaries between nature and human life.

This model has largely failed. Wildlife corridors are essential for genetic diversity and migration. Fences fragment ecosystems. The modern approach accepts that animals will move.

It focuses on mitigation and compensation. It is about providing tools and economic incentives that make coexistence worthwhile. The challenge is to ensure that the farmer who loses livestock is not left impoverished.

This requires robust, transparent mechanisms for support. It is a fight that demands empathy and economic justice, not just ecological science.

Non-Lethal Barriers and Behavioral Change

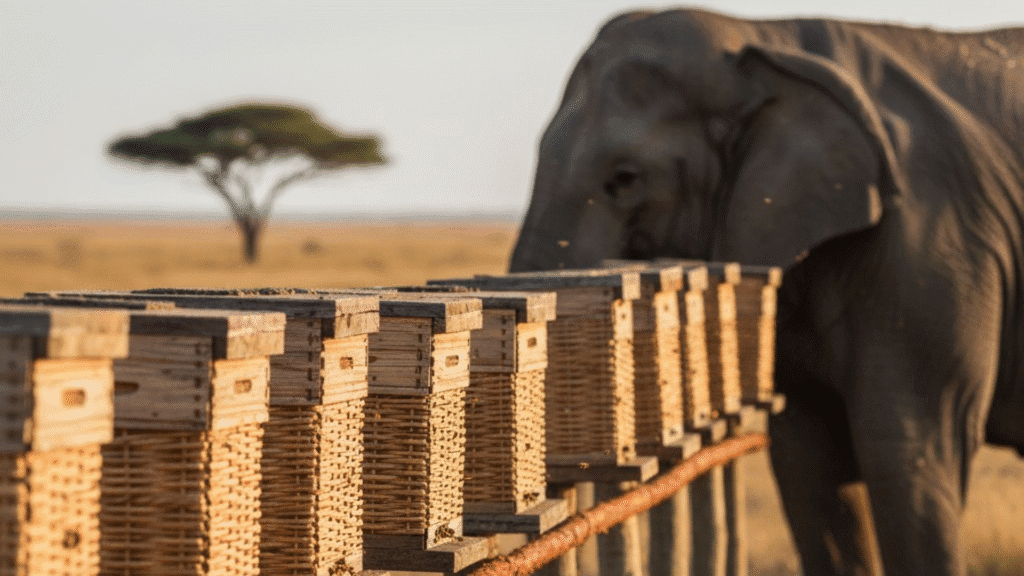

Communities on the frontline are deploying highly effective, non-lethal technologies to deter wildlife. One of the most widely adopted is the beehive fence. Elephants, despite their size, fear African honey bees.

They associate the buzzing sound with pain, especially around their sensitive trunks. Local conservation groups have helped communities install beehive fences along the borders of their farms. These are simple structures.

They consist of suspended beehives connected by a wire. If an elephant touches the wire, the hives swing and the bees are disturbed. This provides an immediate, natural deterrent.

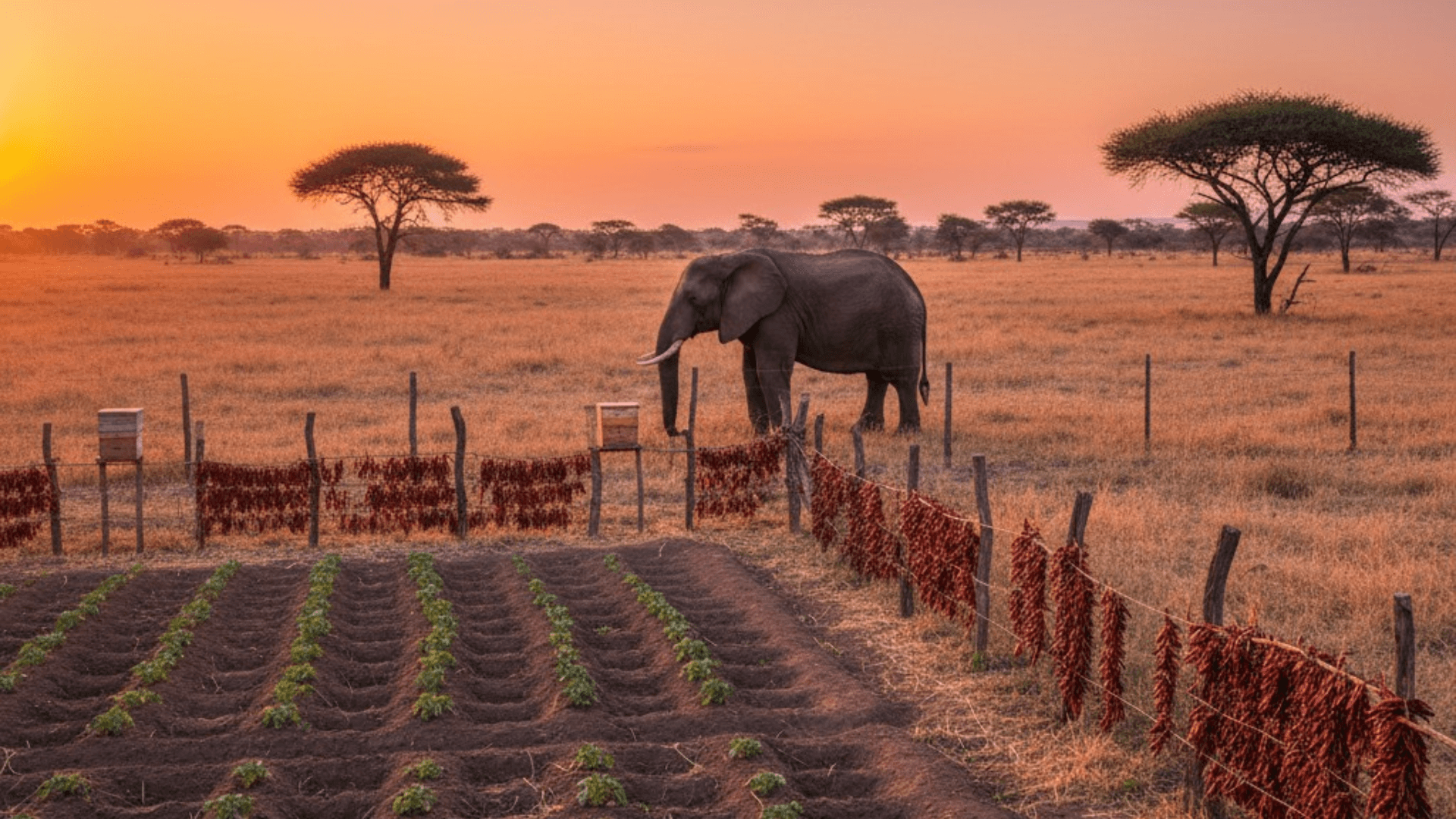

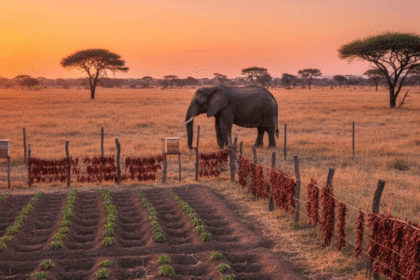

It protects the crop without harming the animal. An added bonus: the communities gain honey. This provides a new income stream. Wildlife, previously a liability, is now a source of profit. Another simple tool is the chili fence.

Elephants hate the smell of capsaicin, the compound that makes chili peppers hot. Farmers mix chili powder with engine grease and smear it onto rope fences. The smell keeps the elephants away.

These behavioral change strategies are preferred. They allow animals to learn to avoid human spaces. They foster a system of mutual respect and spatial awareness.

The deployment of simple, smart technology like GPS collars on problem animals also helps. This allows communities to be alerted when a herd is approaching. This early warning system saves both crops and lives.

From Conflict to Compensation and Insurance

The shift from mitigation to full economic buy-in requires financial solutions. Conservation insurance schemes are emerging as a critical tool. They function like basic insurance policies.

Community members pay a small premium. They are compensated fairly if they lose livestock or crops to protected wildlife. This transfers the economic risk from the individual farmer to a collective fund. It is often backed by conservation organizations.

This compensation is transformative. It removes the immediate, emotional impulse to retaliate against a predator. The farmer no longer views the lion as a threat to survival. They see the wildlife as an asset to be protected.

The focus is also on revenue sharing. Local communities demand a larger share of the profits from luxury tourism. When money from park entry fees and safari lodges flows directly back to community schools, clinics, and infrastructure, the attitude changes.

The wildlife becomes the asset that funds their development. The community becomes the fiercely protective custodian of the natural resource. This economic alignment is the single strongest driver for lasting coexistence.

The Role of Local Governance and Education

The success of coexistence models ultimately depends on local governance. Conservation decisions must be made in consultation with the people affected by them. Community conservancies are a rising model. Local communities manage the land themselves.

They own the resource. They decide how much land is dedicated to wildlife corridors. They decide how tourism revenue is spent. This sense of ownership is key to accountability and sustainability. Education also plays a vital role.

Children in these communities are taught the value of their natural heritage. They learn that the elephant and the lion are not just pests. They are a unique resource that drives their local economy.

This instills a sense of pride and stewardship in the next generation. The challenge of human-wildlife conflict is a daily battle. But the quiet successes are mounting.

They are demonstrating a powerful principle: effective conservation is fundamentally a story of human development. It is about ensuring that those who bear the greatest cost of living with nature also receive the greatest benefit.

Daj svoj stav!

Još nema komentara. Napiši prvi.